“Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

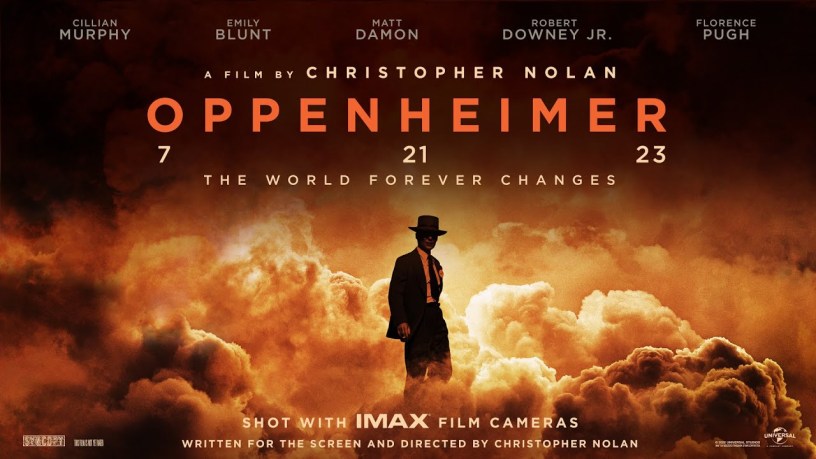

That Oppenheimer was riding on humongous hype would be an understatement, and that’s even before considering the whole Barbenheimer phenomenon. This is a movie by Christopher Nolan after all, one of the foremost auteurs of our time, one of those rare directors who manages to fuse the commercially viable with intellectually appealing masterpieces to create box office behemoths which demand something from the audience as well. His last film, Tenet, was the rare big budget movie which was released and did reasonably well in the midst of a pandemic afflicted time. If it seemed slightly underwhelming, that was only by his own stratospheric standards.

Another reason for the hype and expectations is, of course, the theme. The movie, framed as a biopic of J. Robert Oppenheimer, is based on one of the defining man-made events/disasters of the twentieth century, one which brought to end a horrific war in its own horrific fashion. Oppenheimer, one of the greatest scientific minds of the time, oversaw the development of the atom bomb as part of the Manhattan Project and was always morally conflicted about the aftereffects of what he helped build. The film is based on American Prometheus, a 2008 biography of Oppenheimer. Parallels to the Prometheus myth are obvious, but it’s probably more Frankenstein that the creator identifies with; his own creation perhaps eventually engulfing him in the rest of his life.

With all the backstory though, how does it hold up as a film, purely on artistic and technical merit? Pretty ridiculously well in fact. In narrative structure, much less convoluted than Nolan’s last two efforts, there are still a couple of timelines in focus here. One is the buildup to Oppenheimer’s eventual recruitment to the Manhattan Project and his life and loves till then, as well as the intricate machinations involved in the project for the testing of the bomb, Trinity. The other, future thread runs in two sections again. In one, we have Oppenheimer subjected to an extended hearing in front of a panel while they pick apart his life story to determine if he had any Communist or Soviet sympathies before giving him a security clearance. In the second one, filmed in black and white, Oppenheimer’s one time colleague, Lewis Strauss (an excellent Robert Downey Jr.), is being reviewed again by a panel to determine his suitability for a role in the federal government. Strauss though has it in for Oppenheimer owing to a perceived former slight and has been actively working behind the scenes to get favorable outcomes in both these incidents. Whether he will succeed in either is something we get to know as the movie progresses.

It is while the Oppenheimer hearing is proceeding that the movie goes into flashback mode to regard events which brough him to this point. The early, sometimes awkward days as he found his mentors at home and in Europe, the onset of the Nazi threat and the women in his life, primarily Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh), a sort of lifelong mistress/obsession, and his beleaguered but strong wife, Kitty (Emily Blunt). And of course, his realization of the inevitability of the bomb. The Germans were trying to get there first, and logic seemed to suggest that the Americans needed to get there sooner. Matt Damon plays Lt. Gen Leslie Groves, a military man in charge of the project and getting Oppenheimer and his team of scientists what they need to get things running as soon as they can. Apart from the Physics, there is a lot of political wrangling going on too, as should be expected considering the stakes and times involved. It all leads up to the pivotal moment in the film, and one which has been talked of quite a bit. The tests prior to the actual deployment of the weapon, called Trinity, in the New Mexico desert in July 1945, in the aftermath of which it is said that Oppenheimer pondered on the verse from the Bhagavad Gita that opens this review. And is a sequence which lives up to the expectations. Moments of pure force and alternating silence combine to form a seminal experience on the big screen and Oppenheimer’s visage during the whole thing and afterwards after the devastation has been wrought, is a mirror into the conflicted soul of warmongering. Allied to his moral ambiguity in its aftermath is his ever-present interest in exploring the different ideologies out there, without committing to any one of them; these factors all come together though to throw him under the surveillance and spotlight of Hoover’s FBI agents in the McCarthy era and the subsequent events.

For the uninitiated, this is a very talky movie. The dialogues fly thick and fast and if one loses track of the scene there would be expositions missed. But the mark of a great director is how he can capture the audience’s interest over the length of such a theme, and he does it beautifully here for the mammoth 3+ hours runtime. The tension and involuntary thrill never let up. We are always invested in the lead character’s actions and his dilemmas, as we are in the central conflict of using the bomb, a potential never-look-back moment in warfare. There is always the moral conundrum at the heart of the action too, one which we experience along with the lead scientist, namely – was the dropping of the bomb utterly necessary? The Germans had already surrendered without any proof of their own version, while the Japanese were almost there too. Was it just a ploy to demonstrate to the Soviets the might of the US firepower? It’s a haunting question, one which we can understand the impact on Oppenheimer’s conscience.

There is a remarkable array of star power in the cast list, some big names on screen only for a few moments. Matt Damon, Robert Downey Jr., Emily Blunt, Florence Pugh, Gary Oldman, Kenneth Branagh and a host of other familiar faces and one has to say this is not a gimmick. They all have given weight and honesty to their characters. There are also some nice takes on the real-life friendship between Einstein (played by Tom Conti) and Oppenheimer. But truly, Cillian Murphy has to be the main draw here. Physically he seems to be a dead ringer for the scientist, but more than that, he embodies the man so rivetingly well that his comparatively slight frame dwarfs the rest of the cast. Always a dependable actor, known mainly for his work on Peaky Blinders, here he comes into his own and wows us.

Does the movie have flaws which make it perhaps not Nolan’s own best work? Minor ones perhaps, but for one, despite all the screentime devoted to him, I didn’t come away feeling I knew much more about Oppenheimer’s motivations for his beliefs or behaviors. So, he supported the Spanish liberation struggle and was interested in learning about the world. He was supposed to be something of a womanizer too. But these things are more told to us than we get any real chance to organically understand in the character. But perhaps, this was a nature of man himself. As Murphy himself put it in this interview to The Guardian, “He was dancing between the raindrops morally. He was complex, contradictory, polymathic; incredibly attractive intellectually and charismatic, but, ultimately unknowable.” Another perceived flaw could be the lack of insight into the people who actually suffered the calamity themselves, the Japanese citizens, mostly civilians, of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. That, I feel, is something to do with the theme and tone of the film; this was always intended as a deep dive into the creator’s mind and angst, a victim of a different sort of his own success.

Perhaps he was. But this film is a towering achievement in itself, one which must be seen and lauded for generations to come, and which hopefully uses the struggle of its subject and one of the most seminal moments in mankind’s history to cause us to reflect on our own folly of power in the face of mortality.